Orang Tionghoa Indonesia

印度尼西亚华人

Where are you from?

No, but where are you really from?

Oh, so where are your parents from then?

What happens when superficial distinctions becomes less apparent and cultural differences less obvious? When you think, feel, act, and grow up with one identity, but are linked to another purely by blood or lineage?

From the biblical plight of Jews to Canaan, to the Vietnamese diaspora across the globe in the 1970’s, oppression has always been a part of the immigration narrative.

Garuda Pancasila, National Emblem of Indonesia

Garuda Pancasila, National Emblem of Indonesia

Systematic differential treatment of Chinese populations in Indonesia began during the Dutch colonial period, in response to booming Chinese populations and their relative economic success. The New Order under Suharto’s rule from 1967-1998 saw policies regarding the ethnic Chinese population focusing on their assimilation, rather than integration into mainstream society.

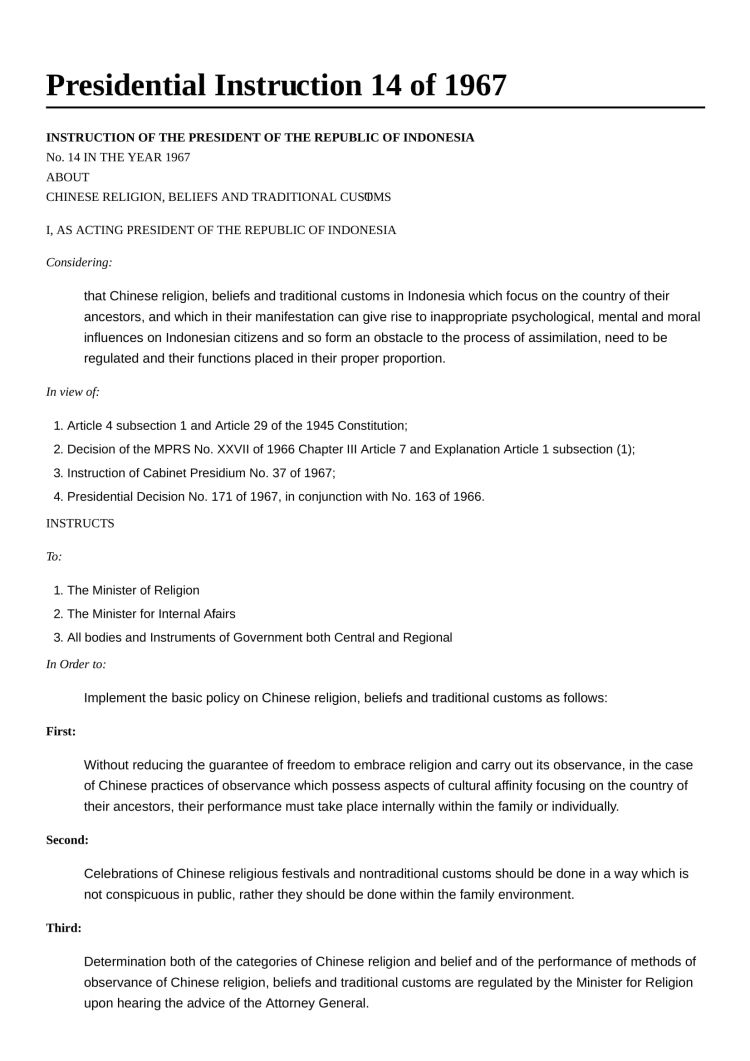

In particular, Presidential Instruction 14 of 1967 on Chinese Religion, Beliefs, and Traditions effectively prohibited instruction of Chinese language in education sectors, and banned public expression of Chinese religions and culture as part of a ‘Basic Policy for the Solution of the Chinese Problem’.

"A new step in the Reformation Era for the Chinese people in Indonesia...they can now celebrate."

Before dawn broke on the Reformation Era under the short-lived presidency of Habibie, successor to Suharto, there was darkness, violence, and dissent.

May 1998 was a chapter of Indonesian history many are still hesitant to recount.

What began as discourse over unemployment and economic hardship due to the recent Asian Financial Crisis, turned into protests and anger directed towards ethnic Chinese Indonesians, who as a class of society were often seen as 'better off', or 'privileged', across the archipelago.

No official figures were recorded, but reports of rape, arson, looting and death were abundant. For Chinese-Indonesian school principal Henny Djunaidi, memories of those events haunt her to this day.

"I was not worried about myself...I was more worried about my family in Jakarta, what would happen to them after I hang up the phone."

According to the 2010 census, Chinese Indonesians account for 1.2 percent of the total Indonesian population, and is the 15th largest ethnic group out of over 600.

Amendment of legal terms segregating "native" and "non-native" Indonesians were passed in 1998 in the wake of the May riot. Prohibition regarding public displays of Chinese cultural practices and language instruction were lifted in 2000, and Chinese New Year was declared a national holiday in 2002.

Yet, conflicting social norms and attitudes persists, owing to centuries of volatile complexity and segregation policies.

"I would look for reason as to why they could be like that...I would fight them."

Experience like these are not confined to times past. Perceivable differences still exist, though younger generations such as Universitas Indonesia student Nadine Btari are much more open to those differences.

It is important to recognise that hostility and cultural differences do not define everyday life of ordinary Indonesians.

Pasar Lama, Tangerang is about an hour away from Jakarta, and has a robust ethnic Chinese population.

Pasar Lama is famous for its Chinese temple, the Boen Tek Bio Temple, built in 1684. It is located just 100 metres away from a mosque.

The international political arena has seen a rise in right-wing populism. Be it resurgence of nationalistic ideals, misunderstanding of different cultures, or fears about employment and sovereign borders. Immigration is often the forefront of political debate.

In Indonesia, the issue of Chinese Indonesians can be especially divisive, given their long history of uncertainty in Indonesian society, and the recent meteoric rise and dramatic fall from grace of a Chinese Christian Jakarta governor.

Agni Malagina, a social sciences researcher specialising in the study of Chinese issues in Indonesia, says issues are often dramatised and politicised.

"You have to understand that the presidential election is coming up [in 2019], and Chinese Indonesian issues can be easily used to create talking points. But in reality, there are very little tension in the communities I studied at the grassroots level"

While immigration is by no means a new concept, our society has become increasingly mobile. The United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs reports that as of 2017, there are now 258 million people living in a different country than other than their country of birth, an increase of 49 percent since 2000.

In particular, Indonesia is host to 346 000 immigrants as of 2017, an increase from 292 000 in 2000.

For Taiwanese expatriate Zheng Yuren, Indonesia was an opportunity. Zheng Yuren moved to Indonesia with his wife, also a teacher, and his young daughter.

He sees hostilities towards Chinese Indonesians as politically motivated, and has not experienced such hostilities in his everyday life.

As for his daughter, Zheng Yuren had this to say.

His daughter Zheng Anzhi was born in Taiwan, but now spends half of each year in Indonesian and half back in her hometown.

So for little Anzhi - where is home?

Special thanks to:

Mr. Bruce Woolley

Mr. Paul Smith

Mr. Sven Fea

Ms. Asty Rastiya

Ms. Hendri Yani

Mr. Edo Juvano

Ms. Nadine Btari

Mr. Alex Martin

Ms. Agni Malagina

Ms. Henny Djunaidi

Mr. Zheng Yuren

Ms. Zheng Anzhi

Mr. Ce Liang

Mr. Kie Nyan

My UQ in Indonesia colleagues

UQ School of Communication and Arts

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade